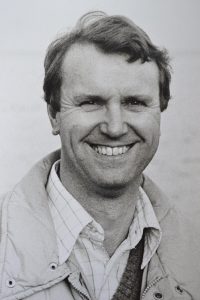

Killer whales, or orcas, are an iconic part of the British Columbia coast. Dr. Michael Bigg, a marine biologist from Duncan, is known as the founder of modern research on killer whales.

Bigg was born in London, England, in 1939, and moved with his family to BC when he was just eight years old. His love of nature was well matched in BC. After graduating high school in Duncan, he went on to get his PhD from the University of British Columbia. Despite later being well known for his research on killer whales, Bigg studied falcons, water shrews and harbor seals in university, and his PhD was based on the reproductive ecology of harbor seals. He earned his PhD in 1972.

Today, there are whale-watching companies that, for a fee, will take you out on a boat for the purpose of seeing whales in the wild. The public has a great love for the instantly recognizable black-and-white whale. But this wasn’t always the case. Prior to the mid-1960s, the public, and even governments, knew next to nothing about killer whales and assumed they were dangerous predators. In the ocean, shooting killer whales was acceptable, and even encouraged.

In the mid-1960s and early 1970s, scientists and the public at large became more interested in the species and developed a desire to learn more about them. The first live capture and display of a killer whale was done in 1964 – a whale named Moby Doll was harpooned off the coast of Saturna Island, one of the Southern Gulf Islands of BC. But Moby Doll wasn’t the only killer whale to be caught – between 1962 and 1973, about 47 killer whales from the BC and Washington coastal areas were captured and kept in captivity. At least 12 killer whales died while trying to be captured. Governments and scientists assumed killer whale populations were plentiful, but if killer whales were going to be considered a harvestable animal, the Canadian government wanted a census completed.

In 1970, Bigg was hired as the head of marine mammal research at the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, BC, and the task fell to him to implement the census.

Bigg started the census by sending out 15,000 questionnaires to boaters, lighthouse keepers, fishermen and any others that frequented the BC coast, and asked them to record all killer whale sightings on one specific day. The results of the questionnaire, which was taken on July 27, 1971, showed the population of killer whales on the BC coast was, at most, 350 – a drastic difference from the thousands of killer whales that were assumed to be in the waters. Similar questionnaires done in the following two years, as well as photo identification, proved the original results were accurate.

In 1976, Bigg sent in his report and indicated that the rate of captures from this small population was unsustainable. He recommended restrictions on capturing killer whales from Canadian waters. Also in 1976, the US National Marine Fisheries Service conducted its own killer whale survey on the Washington coast, and found similar low numbers. With these results on both sides of the border, the public opinion began to turn against capture and captivity. Since 1976, no other killer whales have been captured from the waters off BC or Washington, with the exception of Miracle, a young killer whale that was found starving and had been inflicted with several bullet wounds.

Organizations still wanting killer whales for public display continued to capture them off the coast of Iceland until 1989, when that country outlawed any further captures. Over time, the number of killer whales in marine parks has begun to decline and only a few small-scale captures have been done off the coasts of Argentina, Japan and Russia.

During their research in the early 1970s, Bigg and his colleagues discovered photo-identification techniques. They figured out that killer whales could be identified in a decent photograph of the animal’s dorsal fin and saddle patch when it comes to the surface. Variations like nicks, scratches and tears on the dorsal fin, as well as the pattern of the white or grey saddle patch, are enough to be able to identify one killer whale from another. This discovery meant killer whales could be counted each and every year, rather than simply estimating the numbers. This also meant researchers could conduct a longitudal study of these individual whales and identify their travel patterns and social relationships in the wild. This revolutionized the way killer whales could be studied. Just a few years previous, any research on killer whales had to be done on captured or dead animals, and the study of living, wild killer whales didn’t exist.

After determining that the left side of the animal would be used to photographic identification, Bigg and his team of photographers and spotters grew to include hundreds of volunteers. In 1975, researchers combed through thousands of photos of killer whales and assembled a catalogue identifying each individual whale in BC’s waters. That catalogue continues to be updated and used today.

Bigg died of leukemia on Oct. 18, 1990, at 51 years old. His ashes were spread in the Johnstone Strait, and more than 30 killer whales appeared to attend the ceremony. The Robson Bight Ecological Reserve, a killer whale sanctuary in the Johnstone Strait, was renamed the Robson Bight/Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve. The reserve is 1,715 hectares in size – 467 hectares upland and 1,248 hectares of foreshore, and includes one of the few rubbing beaches known in the world, where killer whales gather and rub against the pebbles under the water.

Because of Bigg and his research, BC’s killer whales have been studied longer than any other marine mammal species on the planet.